The dispute over the South China Sea hit international headlines again on July 12 2016 with the publication of the much-awaited award in the arbitration between the Philippines and China. Does this bring the curtain down on the dispute? To understand what has happened we need first to consider the background to both the dispute and the arbitration.

The dispute over the South China Sea hit international headlines again on July 12 2016 with the publication of the much-awaited award in the arbitration between the Philippines and China. Does this bring the curtain down on the dispute? To understand what has happened we need first to consider the background to both the dispute and the arbitration.

Claims over the South China Sea

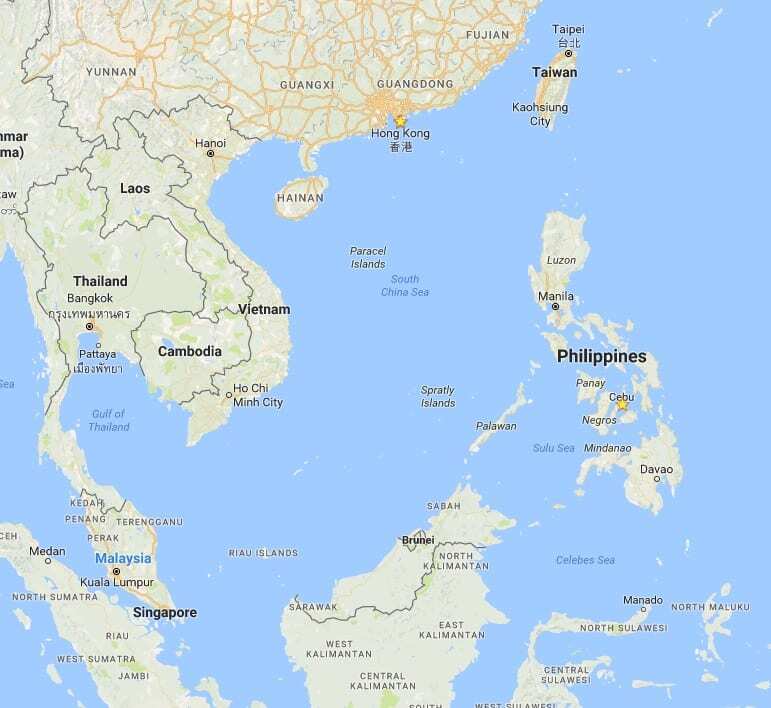

In a nutshell, China claims sovereignty over practically all of the sea based on the infamous “nine-dash line”. Despite claiming ancient historic title to the sea, the first known appearance of the nine-dash line was only in December 1947, on a map to advance China’s claims after WWII when the return of islands occupied by Japan was discussed.

Other claimant nations have staked their claims by reference to international law and by occupying and building on islands and reefs. For example, the Philippines grounded a vessel on Second Thomas Shoal to state its claims, and a few marines now live on the vessel.

Background to the Case

The game changer bringing the dispute between China and the Philippines to a head has been the pace and aggression with which China has been trying to enforce its claims through reclamation and military construction, which includes building on Mischief Reef situated within 200 nautical miles of the Philippines. This prompted the Philippines to commence the arbitration against China.

The case was commenced under the procedure set out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS had been negotiated for nearly a decade, and finally became effective in 1992. China had taken part in the negotiations, and itself ratified the convention in 1996, therefore being bound by its provisions.

UNCLOS did not decide issues of sovereignty over any area, rather it set down a system governing the rights and obligations of states to certain areas of the sea. It gave coastal states an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles from their coastline. It determined which features (e.g. rocks, islands etc…) can generate an EEZ. It put an obligation on all states to preserve the marine environment. Finally, it set down a detailed dispute resolution mechanism for disputes between states under UNCLOS.

As UNCLOS does not touch on sovereignty, no arbitration under UNCLOS can decide an issue of sovereignty. China’s chief (and wrong) argument for saying the Tribunal lacked jurisdiction in this case, and refusing to participate in the proceedings, was that it was trying to do just that.

China’s non-participation did not mean that the award would automatically be in the Philippines’ favour, simply that China would not actively produce evidence and arguments. The Philippines still had to prove their case was correct.

What did the Award decide?

So we have a claim based upon the nine-dash line and various acts of muscle-flexing, on the one side, contending with a system based on UNCLOS on the other.

Having considered all the evidence, the Tribunal made a unanimous decision in favour of the Philippines. The award is binding and unappealable.

The award essentially decided three things: –

- If China had ever held historic rights in what was now (post-UNCLOS) the Philippines’ EEZ then those rights would have been extinguished upon China’s choice to accede to UNCLOS. It follows that the Philippines has exclusive rights to the development of resources within its EEZ (including Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal). Chinese actions within the Philippines EEZ are therefore a direct violation of Philippines’ rights.

- Even if any historic rights had not been extinguished by UNCLOS, then there was no evidence that China had exercised the exclusive historic rights over any waters required to give it exclusive rights. Evidence showed that fishermen of many nations had traditionally used the same waters. There would therefore have been no legal basis for China to rely on historic rights to exclude others in areas over which China was not sovereign.

- Even if China was successful in its claims of sovereignty over islands it claimed based on the nine-dash line (which of course was not decided), China would only be entitled to a maximum 12-nautical mile exclusion zone immediately around such islands, and not 200 nautical miles, as none of the islands or reefs claimed by China are capable of generating an EEZ on their own, under UNCLOS.

In essence therefore this was a victory for the Philippines and for the other coastal states in the South China Sea dispute against China, and for freedom of navigation. China can legally at best only exclude anyone for up to 12 nautical miles from the islands and reefs it claims. Coastal states can assert their exclusive rights in their own EEZ’s against China.

Will the decision change things?

The award does not decide that the nine-dash line itself is illegal, or that China is not allowed to claim sovereignty over places outside any other nation’s EEZ. Nor does it say that China cannot build on reefs and islands it claims as its own (although it did say that by building as it did China had broken its obligations to preserve the environment).

As such, China can keep building and maintaining its nine-dash line to claim rights over all areas of the South China Sea not in any other nation’s EEZ, even though UNCLOS makes clear it cannot under UNCLOS claim more than 12 nautical miles. China will no doubt maintain its position.

It remains to be seen if China’s behaviour in relation to overflight and freedom of navigation exercises will change, or how it will now deal with its base at Mischief Reef which is clearly in the Philippine EEZ. Events since the award would seem to suggest there will be no change in policy.

Finally, what does all this mean for yachting in the South China Sea? No doubt sailing close to islands and reefs claimed by China might earn a stern reaction. So, unless you want to risk being boarded or rammed by the Chinese Coast Guard, or worse, it would still be sensible to give Chinese claimed reefs and installations a wide berth. Not doing so, and justifying that by reference to the 12 July award will not likely get you very far!

Content kindly provided by: Mr. Steffen Pedersen

Steffen.Pedersen@thomascooperlaw.com

![]()